In a first, mouse eggs grown from skin cells

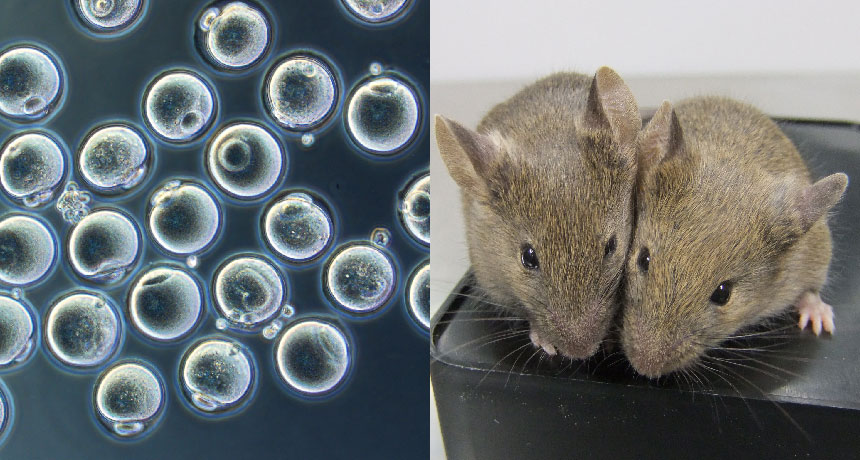

For the first time, researchers have grown eggs entirely in a lab dish.

Skin-producing cells called fibroblasts from the tip of an adult mouse’s tail have been reprogrammed to make eggs, Japanese researchers report online October 17 in Nature. Those eggs were fertilized and grew into six healthy mice. The accomplishment could make it possible to study the formation of gametes — eggs and sperm — a mysterious process that takes place inside fetuses. If the feat can be repeated with human cells, it could make eggs easily available for research and may eventually lead to infertility treatments.

“This is very solid work, and an important step in the field,” says developmental biologist Diana Laird of the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the study. But, she cautions, “I wouldn’t want patients who have infertility to think this can be done in humans next year,” or even in the near future.

Stem cells reprogrammed from adult body cells have been coaxed into becoming a wide variety of cells. But producing eggs, the primordial cells of life, is far trickier. Egg cells are the ultimate in flexibility, able to create all the bits and parts of an organism from raw genetic instructions. They are far more flexible, or potent, than even the embryonic-like stem cells from which the researchers created them.

Making eggs in a dish is such a difficult task that it required a little help from ovary cells that support egg growth, stem cell researcher Katsuhiko Hayashi of Kyushu University in Fukuoka, Japan, and colleagues found. The team had previously reprogrammed stem cells to produce primordial germ cells, the cells that give rise to eggs. But they had to put those cells into mice to finish developing into eggs in the ovary (SN: 11/3/12, p. 14).

It’s unclear how support cells in ovaries foster egg development, Hayashi says. Something made by support cells or physical contact with them, or both, may be necessary for the egg to fully mature. Researchers can’t yet reproduce the supporting cells in the lab and so need to get those cells from embryos, Hayashi says. That could be a problem when trying to replicate the experiments in humans.

Hayashi and colleagues made artificial ovaries to incubate the lab-grown eggs by extracting ovarian support cells from albino mouse embryos. The researchers then mixed in primordial germ cell‒like cells created from tail-tip skin cells from a normally pigmented mouse. After 11 days in the lab dish, the eggs were mature and ready for fertilization. That’s about the same time it takes for eggs to mature in a mouse ovary, Laird says. That means researchers may need patience to make human eggs in lab dishes. “It could be a nine- to 12-month differentiation process in humans,” she says.

Researchers fertilized the eggs and transplanted the embryos into the uteruses of female mice. In that experiment, six pups with dark eyes were born, indicating that they came from the tail-tip eggs and not eggs accidently extracted from the albino mice along with the support cells. The baby mice grew up apparently healthy and have produced offspring of their own.

Growing quality eggs in the lab may be an all-or-nothing exercise. In another experiment using eggs made from embryonic stem cells, the researchers found that some genes weren’t turned on or off as in normal eggs. And only 11 of 316 embryos made from those lab-grown eggs grew into mouse pups. Some of the embryos didn’t make it because they had abnormal numbers of chromosomes, indicating that the eggs weren’t divvying up their DNA properly.

The low success rate implies that only one in every 20 lab-grown eggs, or oocytes, is viable, Hayashi says. “This means that it is too preliminary to use artificial oocytes for clinical purposes. We cannot exclude a risk of having a baby with a serious disease. We still need to do basic research to refine the culture conditions.”