CRISPR gene editing relieves muscular dystrophy symptoms in dogs

Gene editing can reverse muscular dystrophy in dogs.

Using CRISPR/Cas9 in beagle puppies, scientists have fixed a genetic mutation that causes muscle weakness and degeneration, researchers report online August 30 in Science.

Corrections to the gene responsible for muscular dystrophy have been made before in mice and human muscle cells in dishes, but never in a larger mammal. The results, though preliminary, bring scientists one step closer to making such treatments a reality for humans, says study coauthor Eric Olson, a molecular biologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is a rare but severe, progressive disease that affects mostly boys and men. People with the disease, which is just one of many types of muscular dystrophy, rarely live past their 20s, usually dying of heart failure. An estimated 300,000 people worldwide suffer from the condition.

The disease can be caused by any number of mutations to the gene that makes the protein dystrophin, which is essential for muscle structure and function. The mutations, which are often clustered in one particular region of the gene, usually stop production of the protein. Gene editing targeting that region could correct for these mutations’ effects, restoring protein production.

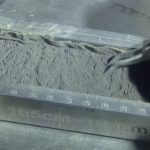

Researchers injected two 1-month-old beagle puppies with a mutation in this hot spot with different doses of a virus carrying the gene-editing machinery. The team then measured dystrophin levels in different muscles after eight weeks.

Levels of the protein increased in every muscle group that the team studied, though the effect was variable. Dystrophin levels in the heart of the dog receiving the higher dose were 92 percent of what they were in healthy pups without the mutation, but levels in the dog’s tongue were only 5 percent of normal.

“It was really gratifying to see the efficiency with which dystrophin was restored after only eight weeks,” Olson says.

Previous studies have suggested that bringing dystrophin levels up to just 15 percent of what they are in healthy people could be enough to relieve some of muscular dystrophy patients’ symptoms. All of the muscles examined (except the tongue) showed at least that level of improvement in both dogs.