A massive net is being deployed to pick up plastic in the Pacific

The days of the great Pacific garbage patch may be numbered.

A highly anticipated project to scoop up plastic from the massive pool of ocean debris is poised to launch its first phase from Alameda, Calif., on September 8. The creators of the project, called the Ocean Cleanup, say their system can remove 90 percent of the plastic in the patch by 2040.

First proposed in a 2012 TED talk by Dutch-born inventor Boyan Slat, who was then just 18 years old, the Ocean Cleanup’s system consists of a snaking line of booms designed to simulate a kind of free-floating coastline that can essentially herd the plastic trash into retrievable piles. The project, based in Delft, the Netherlands, has drawn more than $30 million in donations from sponsors, philanthropists and a crowdfunding campaign.

It has also drawn the ire of researchers who worry about possible negative effects on ocean life, or who say the project doesn’t address the majority of ocean plastic — bits called microplastics that are smaller than half a centimeter. The system is designed to capture pieces of plastic ranging in size from a few millimeters to tens of meters across, such as fishing nets. Critics also worry the project will divert attention and money from the root of the problem: too much plastic waste in the first place.

Ready for launch

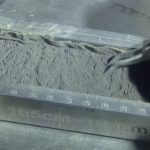

A March study in Scientific Reports, led by Ocean Cleanup’s lead oceanographer Laurent Lebreton, estimated that in 2015 the great Pacific garbage patch was scattered across some 1.6 million square kilometers — an area twice the size of Texas — within a vast ocean swirl known as the North Pacific gyre. The patch, the study found, contains about 1.8 trillion pieces of debris, largely consisting of buoyant plastics like polyethylene and polypropylene, floating at the surface (SN Online: 3/22/18). Most of those pieces are smaller than half a centimeter — but by mass, more than 90 percent of the patch is made up of pieces 5 centimeters or bigger, the scientists estimate.

It’s those larger pieces that the cleanup system will snag. The system features a 600-meter-long line of unmoored booms that act as an artificial shoreline traveling with the wind, waves and ocean currents while rounding up plastic debris. Beneath the surface, the booms drag a 3-meter-long skirt, through which only the tiniest bits of plastic can escape. Currents will naturally push the line of booms into a u-shape, herding plastic particles so they’re easier to collect.

The booms are also tricked out with solar-powered lights, anti-collision systems and satellite antennas to avoid vessels and help project scientists keep track of the system’s location. Periodically, support vessels will cart the collected plastic bits back to land for recycling.

The September 8 launch of “System 001” will be a beta test for the first of a planned fleet of about 60 such systems, though parts of a system have been tested for durability and performance in the North Sea and off California. Once launched, System 001 will undergo two weeks of field testing off the California coast, Lebreton says. If all goes well, it will head to the North Pacific gyre, arriving within five weeks of the launch date. “We’re hoping to bring the first plastic back before the end of the year,” he says.

Once the full fleet is launched, Ocean Cleanup says, it could remove 50 percent of the plastic in the patch within five years, and 90 percent by 2040.

Do no harm

Because the great Pacific garbage patch lies within international waters, no environmental impact assessment is required for launching the apparatus. Still, the foundation says it commissioned an assessment from an independent consultant group, published in July. The report, which focused on how the system might affect marine life, found no reasons for serious concern but identified one moderate concern: that sea turtles might be drawn to the system and then ingest the plastics.

But there are many concerns not covered by the assessment, says Kim Martini, a physical oceanographer at Seattle-based Sea-Bird Scientific, which makes instruments that measure ocean properties. In a January 2017 piece on the oceanography blog Deep Sea News, Martini outlined other worries including whether the sweeping net could accumulate marine hitchhikers, from algae to barnacles and other kinds of critters, adding drag and stress that could alter the hydrodynamics of the system. There’s another question, Martini says, in whether herding the plastic will promote new, tiny ecosystems among the trash — possibly attracting even more wildlife to the area (SN: 2/20/16, p. 20). “Are they going to start scooping that up?”

Can it even work?

Despite previous test deployments, Martini says, there’s also no evidence yet that the system can actually collect much plastic. “This [deployment] is the real litmus test. So we’ll see.”

Environmental scientist Marcus Eriksen at the Los Angeles–based nonprofit 5 Gyres Institute also doubts the system will collect as much plastic as the project scientists claim. A 2014 study in PLOS ONE that he coauthored with Lebreton said many of the estimated 5 trillion bits of ocean plastic worldwide are quickly removed from surface waters by natural forces.

“There’s a lot of beaching, shredding, sinking of the debris,” so that many of the small particles would have now sunk below the project’s 3-meter-deep skirt, Eriksen says.

Meanwhile, new particles are always entering the ocean. Eriksen says that’s why 5 Gyres and other conservation organizations are focused on prevention as the most effective cleanup strategy: persuading people to use less plastic in the first place. “If you want to mitigate the harm, it’s really upstream.”

Every effort helps

The Ocean Cleanup representatives say their project is meant to work in concert with such upstream measures. Even while trying to change human behavior, the team argues, it’s still worth trying to remove whatever is already out there floating near the surface.

“The whole point is that we want to try to collect as much as possible,” Lebreton says.

Whatever the result of this deployment, some groups trying to tackle the plastic trash problem applaud the Ocean Cleanup for raising awareness around the issue.

“I love how passionate people are about the Ocean Cleanup project,” says Adam Lindquist, the director of Baltimore’s Healthy Harbor Initiative. His group installed a pair of moored but floating “water wheels” with booms and skirts — nicknamed Mr. Trash Wheel and Professor Trash Wheel — at two river mouths in the city’s inner harbor. In four and a half years, the two have scooped up some 900 tons of debris, from contact lenses to mattresses, in an effort to catch the trash before it enters the ocean.

“Any tech that’s removing plastics from the ocean is a good thing,” Lindquist says. “But the actual worth is getting people to take the problem more seriously, so that we can move toward real solutions — like source reduction.”