DNA from Beethoven’s hair hints at what killed the composer

DNA from strands of Beethoven’s hair is helping to uncover what may have caused his death, researchers say.

The composer was plagued with health issues for most of his life. On March 26, 1827, he succumbed to what many historians suspect was liver failure while in his apartment in Vienna. Now, an analysis of several locks of hair passed down through families and gathered by collectors shows that Beethoven carried several genetic risk factors for liver disease, the scientists report March 22 in Current Biology.

This elevated risk — paired with a potential liver infection and the composer’s alleged drinking habits — may have hastened Beethoven’s premature death at the age of 56, says Tristan Begg, a biological anthropologist at the University of Cambridge.

It’s well-known that Beethoven’s storied career was cut short by progressive hearing loss that left the composer completely deaf by age 45. Beethoven also suffered from gastrointestinal issues and a deteriorating liver. That faulty organ is thought to be responsible for the composer’s skin reportedly turning yellow in the summer of 1821.

The root cause of Beethoven’s plethora of health issues has been a source of fascination to many. But working out what ailed a man that lived nearly two centuries ago is no easy task. Researchers have had to rely on notes from the composer’s two autopsies, preformed after he was exhumed in 1863 and 1888, and other historical documents.

Clues, however, could hide in Beethoven’s DNA. Only a few historical figures — such as Richard III — have had their DNA analyzed (SN: 12/2/14). But these genetic treasure troves can provide information that “no anatomical examination, after two hundred years, could provide,” says Carles Lalueza-Fox, a paleogeneticist at the Institute of Evolutionary Biology in Barcelona, who was not involved in the study.

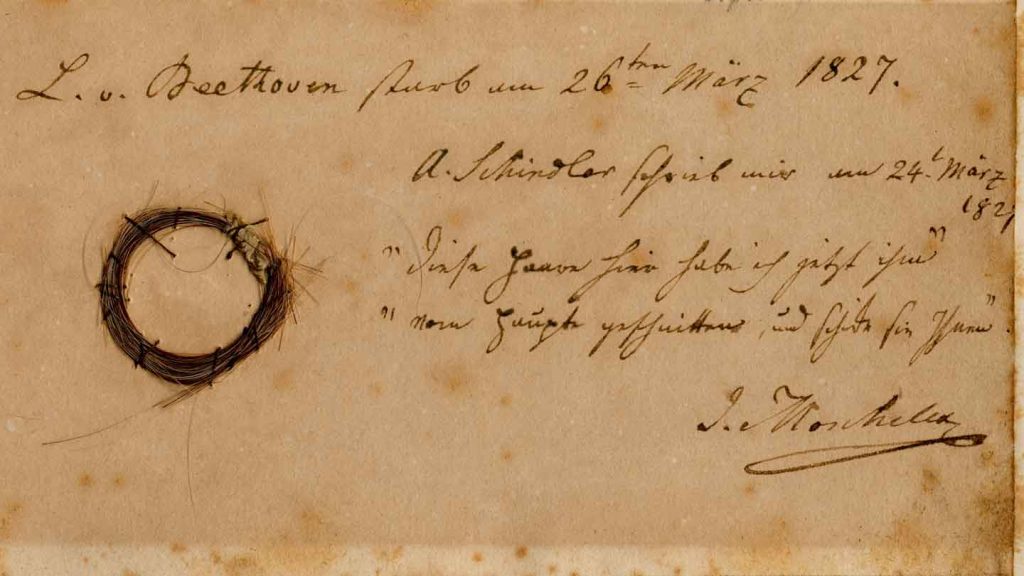

In 2014, Begg and his colleagues decided to reconstruct Beethoven’s genetic instruction book, or genome. First, the team needed a piece of the composer himself. Luckily, around 30 separate locks of hair attributed to Beethoven had survived, in the possession of collectors and the descendants of people who first received the hair in the 19th century.

Begg partnered with Beethoven enthusiasts to ask the owners of these locks to part with a few strands. The team was able to gather samples from eight locks said to have been snipped from 1821 to 1827.

One lock didn’t yield enough DNA for analysis. Of the others, two locks could not have come from the composer; one belonged to a woman with an ancestry consistent with Ashkenazi Jews, the researchers found. But five of the locks, which came from various sources, clearly belong to a single individual with central European ancestry, which Beethoven would have had. The natural degradation of DNA over time in these locks was also consistent with the hair dating to the early 19th century.

Those common features — along with a clear record of who owned these separate locks of hair over the centuries — makes Begg “extremely confident” that these locks are Beethoven’s.

Lalueza-Fox agrees. “I think they provide compelling evidence of five samples being from the composer,” he says.

The researchers used some of the best-preserved locks to reconstruct the composer’s genome. This analysis didn’t uncover any genetic markers for deafness or intestinal issues. But the team did identify several risk factors for liver disease, including a variant of the gene PNPLA3 that would have tripled the composer’s risk of developing liver issues in his lifetime.

Those risk factors alone shouldn’t have doomed Beethoven. But the scientists also found traces of the hepatitis B virus, which damages livers, in one of the strands reportedly collected shortly after Beethoven’s death. The risk to the liver from a hepatitis B infection would have been further compounded by regular alcohol use, the researchers say. Some contemporaries claimed that the composer was drinking heavily by the end of his life.

While we don’t know exactly what combination of factors killed Beethoven, “this is a fascinating detective story,” says Ian Gilmore, a hepatologist at the Royal Liverpool University Hospital in England, who was not involved with the research.

A fascinating story with a new twist: The Y chromosome in the five hair samples doesn’t match those of five people who share a 14th century ancestor with Beethoven. (The composer never had any known children.) This could be a sign that the hair is inauthentic. Or, more likely, one of Beethoven’s direct ancestors on his father’s side had a child outside of marriage, possibly sometime between the 14th and 16th centuries, Begg says.