‘The Dawn of Everything’ rewrites 40,000 years of human history

Concerns abound about what’s gone wrong in modern societies. Many scholars explain growing gaps between the haves and the have-nots as partly a by-product of living in dense, urban populations. The bigger the crowd, from this perspective, the more we need power brokers to run the show. Societies have scaled up for thousands of years, which has magnified the distance between the wealthy and those left wanting.

In The Dawn of Everything, anthropologist David Graeber and archaeologist David Wengrow challenge the assumption that bigger societies inevitably produce a range of inequalities. Using examples from past societies, the pair also rejects the popular idea that social evolution occurred in stages.

Such stages, according to conventional wisdom, began with humans living in small hunter-gatherer bands where everyone was on equal footing. Then an agricultural revolution about 12,000 years ago fueled population growth and the emergence of tribes, then chiefdoms and eventually bureaucratic states. Or perhaps murderous alpha males dominated ancient hunter-gatherer groups. If so, early states may have represented attempts to corral our selfish, violent natures.

Neither scenario makes sense to Graeber and Wengrow. Their research synthesis — which extends for 526 pages — paints a more hopeful picture of social life over the last 30,000 to 40,000 years. For most of that time, the authors argue, humans have tactically alternated between small and large social setups. Some social systems featured ruling elites, working stiffs and enslaved people. Others emphasized decentralized, collective decision making. Some were run by men, others by women. The big question — one the authors can’t yet answer — is why, after tens of thousands of years of social flexibility, many people today can’t conceive of how society might effectively be reorganized.

Hunter-gatherers have a long history of revamping social systems from one season to the next, the authors write. About a century ago, researchers observed that Indigenous populations in North America and elsewhere often operated in small, mobile groups for part of the year and crystallized into large, sedentary communities the rest of the year. For example, each winter, Canada’s Northwest Coast Kwakiutl hunter-gatherers built wooden structures where nobles ruled over designated commoners and enslaved people, and held banquets called potlatch. In summers, aristocratic courts disbanded, and clans with less formal social ranks fished along the coast.

Many Late Stone Age hunter-gatherers similarly assembled and dismantled social systems on a seasonal basis, evidence gathered over the last few decades suggests. Scattered discoveries of elaborate graves for apparently esteemed individuals (SN: 10/5/17) and huge structures made of stone (SN: 2/11/21), mammoth bones and other material dot Eurasian landscapes. The graves may hold individuals who were accorded special status, at least at times of the year when mobile groups formed large communities and built large structures, the authors speculate. Seasonal gatherings to conduct rituals and feasts probably occurred at the monumental sites. No signs of centralized power, such as palaces or storehouses, accompany those sites.

Social flexibility and experimentation, rather than a revolutionary shift, also characterized ancient transitions to agriculture, Graeber and Wengrow write. Middle Eastern village excavations now indicate that the domestication of cereals and other crops occurred in fits and starts from around 12,000 to 9,000 years ago. Ancient Fertile Crescent communities periodically gave farming a go while still hunting, foraging, fishing and trading. Early cultivators were in no rush to treat tracts of land as private property or to form political systems headed by kings, the authors conclude.

Even in early cities of Mesopotamia and Eurasia around 6,000 years ago (SN: 2/19/20), absolute rule by monarchs did not exist. Collective decisions were made by district councils and citizen assemblies, archaeological evidence suggests. In contrast, authoritarian, violent political systems appeared in the region’s mobile, nonagricultural populations at that time.

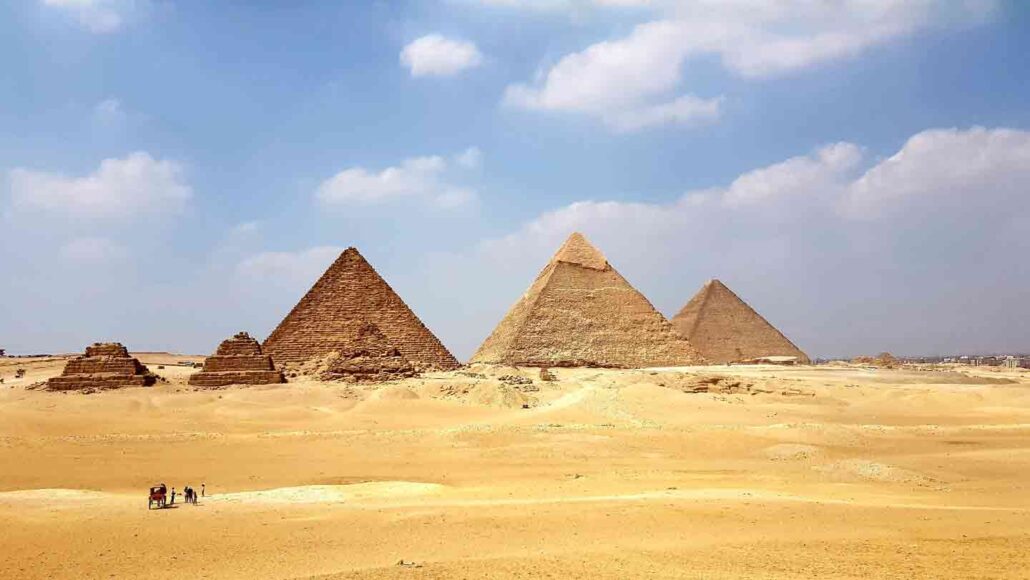

Early states formed in piecemeal fashion, the authors argue. These political systems incorporated one or more of three basic elements of domination: violent control of the masses by authorities, bureaucratic management of special knowledge and information, and public demonstrations of rulers’ power and charisma. Egypt’s early rulers more than 4,000 years ago fused violent coercion of their subjects with extensive bureaucratic controls over daily affairs. Classic Maya rulers in Central America 1,100 years ago or more relied on administrators to monitor cosmic events while grounding earthly power in violent control and alliances with other kings.

States can take many forms, though. Graeber and Wengrow point to Bronze Age Minoan society on Crete as an example of a political system run by priestesses who called on citizens to transcend individuality via ecstatic experiences that bound the population together.

What seems to have changed today is that basic social liberties have receded, the authors contend. The freedom to relocate to new kinds of communities, to disobey commands issued by others and to create new social systems or alternate between different ones has become a scarce commodity. Finding ways to reclaim that freedom is a major challenge.

These examples give just a taste of the geographic and historical ground covered by the authors. Shortly after finishing writing the book, Graeber, who died in 2020, tweeted: “My brain feels bruised with numb surprise.” That sense of revelation animates this provocative take on humankind’s social journey.